In the second panel session from Left Lockdown Sceptics London Feb 2022 meeting, Dr Sunetra Gupta, Dr Jay Bhattacharya & Dr Martin Kuldorff discuss The Great Barrington Declaration, and the devastating impacts of lockdowns on the most deprived in society and the Global South, followed by an audience Q&A, You can find the first panel session ‘The Selling of Health and Immunity’ here and an overall summary of the day here.

Contents:

Introductory remarks

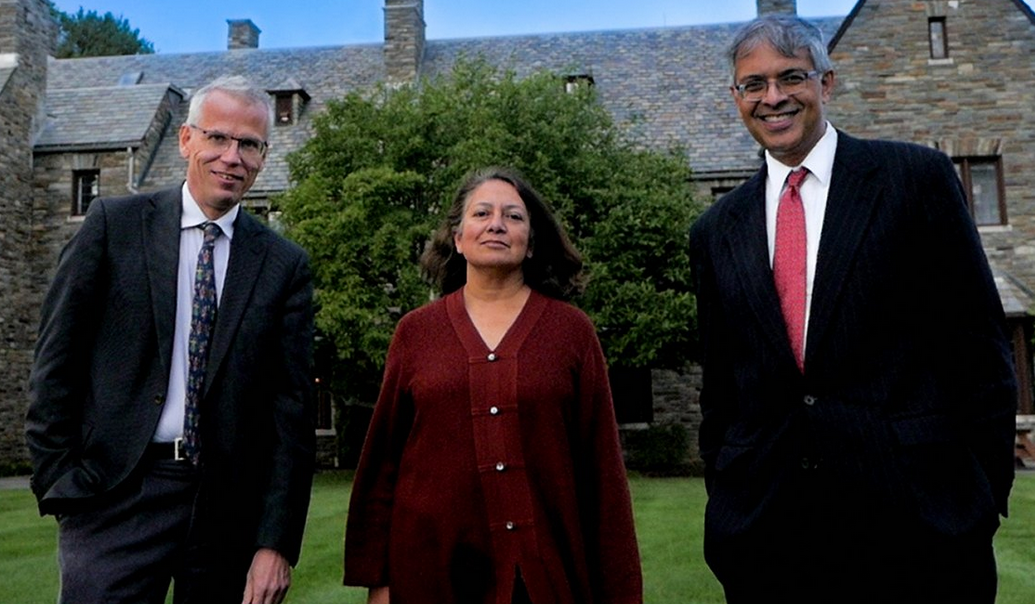

Chair: We are so pleased to have Professor Sunetra Gupta at this session: ‘The Vindication of the Great Barrington Three’ along with GBD co-founders Martin Kulldorff and Jay Bhattacharya. One of the reasons we are here today is because the Great Barrington Declaration was able to kick off the challenge to whole population lockdowns and explain that focused protection of the frail, elderly and people most at risk of COVID made most sense. That was controversial. They were attacked for being ‘bad epidemiologists’ (as opposed to Neil Ferguson, who we were told was the best epidemiologist). They are of course three of the most eminent epidemiologists in the world, working respectively at Oxford, Harvard, and Stanford, but they were attacked for their modelling, as well as attacked for being, interestingly enough, Right Wing. That politicization of science will be a theme throughout the day.

Professor Gupta is a professor of Theoretical Epidemiology at the University of Oxford. She has undertaken research in a range of infectious diseases, including malaria, COVID, and meningitis. She was awarded the 2007 Scientific Medal by the Zoological Society of London and the 2009 Rosalind Franklin Medal. As an early lockdown sceptic, it’s hard to convey how much kind of support and intellectual comfort that the Great Barrington Declaration gave somany of us who felt that finally, our voices and our concerns werebeing addressed from a high level. So, without further ado, I’m going to pass it over to Professor Gupta.

Dr Sunetra Gupta

Dr. Gupta: Thank you. It’s a particular pleasure to be here, because of the discomfort that I’ve had to endure being called ‘Right Wing’ when I’ve always considered myself very much to be on the left of the left if anything. So it’s good to be here.

Now, vindication is quite a strong word. We need to be very careful not to be too triumphant. So I’m going to use it more as a framework to discuss the GBD, where I think it came from, the chair has already given us a pretty good introduction, and to try and understand why it was dismissed in the way that it was.

The GBD was essentially a strategic statement. People criticize us on the finer points; ask why didn’t we lay out exactly how it was to be enacted. But a fundamental point that people fail to appreciate was that it was a strategic statement. The way that it would be implemented in different locations had to be worked out specifically within those settings. Its primary proposition, really, was that lockdowns and some of the other restrictive and highly imaginative measures that followed were utterly inappropriate as tools to deal with the pandemic. There are three parts to why we felt that; different levels of uncertainty attached to each of these parts. Firstly there was considerable uncertainty regarding the purpose of these lockdowns. What were they actually trying to achieve? Zero Covid, for all its insanities, is logically a sound enough proposition, that maybe if you Locked Down you get to Zero Covid. (Though as we know it has all kinds of other problems.)

But what else can you achieve with a lockdown? The supposition of the non-Zero COVID crowd was that you could suppress infection. You can’t: there’s only a few things you can do with any kind of intervention. You can either get rid of the pathogen – unrealistic – or you can try and suppress it. But if you suppress it for a particular period of time, it’s going to come back again. Can you suppress it until you get a vaccine? Do you know when a vaccine might be available? There was a lack of strategy, lack of clear thinking, and a lot of uncertainty regarding their purpose and, more importantly, their effectivity. Would a plan like zero COVID be realizable? There was a big question mark surrounding that in October 2020.

By contrast, we had a fairly high level of certainty about how the virus would play out and other properties of the virus because SARS COV-2 is very firmly and clearly a member of the coronavirus family. It’s a beta coronavirus. There are four coronaviruses circulating, two of them are beta coronaviruses, OC43 and HKU1. These are viruses that we live with. We know exactly how they work. We know they elicit immunity, which lasts permanently or for a long time against severe disease itself but is not durable when it comes to infection. So, we knew that this virus was likely to do the same thing. Infection blocking immunity would be for a short duration: But the first infection would give you good protection against severe disease and death for those who are vulnerable.

We knew how it was likely to play out. We knew that, once passed through its epidemic phase, this virus would make a journey towards an endemic state, such as we enjoy with the other coronaviruses. About that we could be fairly certain. We could not be sure that lockdowns caused harm affecting those not in the privileged position of being able to work from home or hold on to their jobs, or schoolchildren stopped from attending school, or vulnerable young adults.

By October 2020, we had witnessed the huge damage Lockdowns had already caused in the Global South. This schedule of uncertainty was actually inverted by those who wished to protect themselves using lockdowns as a measure, those who had the luxury of being able to endure lockdown. On each of these three points, this was inverted. What we were most uncertain about–whether these measures worked–they treated as if absolutely settled. That there was no doubt whatsoever that these lockdowns would work to suppress infection, even though they didn’t even have a clear strategy of what that was. The zero COVID people acted as if there was absolutely full certainty that these measures would eradicate the disease, even though that was pretty unlikely.

The second point which we got attacked on, especially through the John Snow Memorandum, was to do with the biology of the virus and its epidemiology. Credible scientists made statements which are highly implausible such as ‘maybe this virus doesn’t give you any immunity at all’. Or patently incorrect statements, such as that because immunity might not be permanent or durable (which is almost herd immunity against infection), that we could not get to an endemic state. That is simply incorrect. With measles and diseases where you have viruses giving lifelong immunity against infection, you get to that endemic state when people stay immune. In the case of coronaviruses, you have to maintain that wall of immunity through repeated infection, but it is no different. The endemic state is still one where there is substantial herd immunity in the population. And that word, herd immunity, was immediately treated as some sort of dirty word–maligned and treated as a synonym for eugenics, which is very peculiar indeed.

The scientists involved in promoting lockdowns downplayed the certainty that we had about these, and amplified the uncertainty regarding how the virus might evolve. In some senses, they’re still using Omicron now as their kind of get out of jail card by saying, ‘oh well, everything’s okay now because we have a variant which is mild’. But that’s not the most likely reason why we are seeing fewer deaths from Omicron. It is because we reached an endemic equilibrium. There is enough herd immunity now and enough exposure in the population, that its effects, the rate of people dying, have diminished in the way that not in its endemic state, the other coronaviruses don’t kill a lot of people.

The third point, that lockdowns did cause harm, was again inverted. Sensible people wrote to me saying, how do you know that lockdowns cause any harm? What’s the evidence? This is what prompted us to set up Charity Collateral Global, to try and document these harms. Because you’re sitting there, facing all these intelligent people saying come on, what’s the big deal with locking down? So we wanted to catalogue the harms very carefully and make sure that we had a repository of that. Also, even for those who acknowledged that there was harm, which became inevitable as time wore on, there was this excuse that was made repeatedly that, well yes, of course, it causes some harm, but it’s unavoidable. So that was another line of attack–and it is our intention through Collateral Global to address that point.

Of course, there were uncertainties. We didn’t know how big the second wave would be. It was peculiar to be attacked then for saying that we thought the epidemic was over, as we were engaged in October 2020 in trying to come up with solutions to the problem. But there was uncertainty about the journey from its epidemic state to endemic equlibrium. Focused Protection was robust to many of these uncertainties. This was then criticized as not being implementable.It’s hard to see why, because certainly in the settings where lockdown was supposed to work, many of the ways that you enact FP were sort of a subset of lockdown.

There was almost no desire at all to engage in discussion about this: Instead, people resorted to derision, and a tribal atmosphere developed within the scientific community, to the extent that even those who advocated FP distanced themselves from the GBD, positing it as some polar extreme from the zero COVID crowd and trying to position themselves more centrally. The actions of these ‘Centrists’ actually did more to promote that kind of tribalism. So some said FP was not possible to implement. Others mischaracterized it entirely as a do-nothing strategy.

It’s true FP requires the individual to do nothing in some ways. Certainly, it deprives them of the possibility of signalling their virtue by putting masks on and walking about. The ‘do-nothing’ applies to the individual, because the Focused Protection strategy transfers that responsibility to the state. And so, characterising FP as do-nothing means ‘you’re not letting me show people that I can do something.’ Which to me is a gross act of crass individualism: A collective individualism which has characterized the response. It signals communitarianism, and yet is in complete opposition to it.

Individualism being cloaked as communitarianism has been one of the biggest problems we’ve faced in trying to get a reasonable discussion going about the harms of lockdown and a reasonable strategy to minimize deaths not just from the pandemic, but all the collateral damage. I think I’ll stop there.

Dr Martin Kulldorff

Dr. Kulldorff: I’ll talk a little bit about the strategic and political situation that we came into. Good morning, everybody. You have just listened to the most pre-eminent infectious disease expert in the world. It has been a great honour to work with Sunetra during these two years. It is amazing that instead of listening to Dr Gupta, people have been smearing and slandering her enormously from the left and the right. And while all three of us have been in that situation, for some reason, Sunetra has been the hardest hit of this slander. So, I really appreciate that you invited not just the three of us, but specifically Sunetra.

The reaction to the GBD has been peculiar. These basic principles of public health should not be controversial. GBD being accused of being some kind of a Right Wing, heartless initiative when nothing isfurther from the truth. Public health should be apolitical. I have never revealed my own political views, but I don’t really care because when I was in my 20s, I worked as a human rights observer in Guatemala, risking my life against the military death squads who were kidnapping and disappearing people. So, I never felt threatened by anybody calling me anything. But one thing that is very disturbing with these attacks is how it undermines the Left.

The GBD has been proven correct. More and more people realize that, so when those who claim to be on the left, claim that this is a right wing thing, it pulls the rug out under what Jay usually calls the honest left. So it’s very important for the left to counter this narrative that FP is something right wing. The US/UK left has completely missed this because they have been pro lockdown.

In my view, in the US, these lockdowns have been the worst assault on the working class and the poor since segregation and the Vietnam War over half a century ago. So it’s important to counter this narrative that lockdowns were ‘left’ and pro-freedoms were ‘right’. The LLS website points out that freedom and the right to speak outagainst censorship has traditionally been a very left position. The rich and powerful can always say what they want. They don’t have censorship. Censorship is used to keep the poor and the working class at bay. And that’s exactly what we are seeing during this pandemic.

I’m from Sweden. The pandemic debates in Scandinavia took a very different approach. All four Scandinavian countries did much less lockdown. Sweden didn’t even close schools, it kept them open throughout the spring of 2020. This was heavily criticized.

So why was Sweden different? One reason is that three of the Swedish countries, Finland, Sweden, and Denmark, during the pandemic were all led by Socialist governments. Norway had a conservative but eventually switched to a Socialist government during the pandemic. One feature of Sweden, is that it’s one of the few Western countries that have a leader, a Prime Minister, who is actually a worker. The Prime Minister (who has just stepped down) was a welder; a member of the Metal Workers Union and on the left.

If you want to illustrate how the left handled this pandemic, you should point to Scandinavia, with Socialist governments who did much better both with less lockdowns and therefore less collateral damage that Sunetra was talking about, but also less COVID deaths than most other Western countries. The narrative that somehow the left was pro lockdown can be countered by saying that actually the governments of Scandinavia were socialist governments who did much better than most other governments.

So those are my views on the strategic issues with this pandemic. But public health professionals care about everybody. I don’t care if people are Democrats, Republicans, or whatever, I care about their lives. I want to save as many people as possible, I want to minimize the deaths from COVID, and I want to minimize the collateral damage. And that’s what FP did. In Florida, the Republican governor DeSantis took the most sane–and most traditional–public health approach, which I supported as the right approach. So that’s just a bit of a strategic background to this.

Dr Jay Bhattacharya

Dr. Bhattacharya: Okay, thank you, Martin. So, I’m Jay Bhattacharya. I am the third founder of the GBD. Someone asked me just recently which of the Beatles I would be. If I were a Beatle. I told them I’d be the stage manager. That’s the role because it is an absolute honour to have written this amazing document with Sunetra Gupta and Martin Kulldorff, two of the most important epidemiologists in the world and from whom I’ve learned tremendous amounts.

As Professor of Medicine at Stanford what I found during the pandemic is that so many of my colleagues, ostensibly on the left, that I thought I shared values with, acted in ways so far outside of what I thought their values were that I still remain shocked. The strategy of lockdowns we followed are the single most illiberal policy I’ve seen in my entire life. And it has burnt at me ever since I first heard of them. One of my very first thoughts, when I heard about this strategy was what damage would be done to the poor around the world.

Lockdowns are the luxury of the rich. They’re luxury of a class of people that thinks that the rest of society should serve them. From the beginning, the Lockdowns required a distinction between essential and non-essential in an almost Orwellian way. Essential workers were essentially the working class. They were called essential, and yet, no matter what their age or risk profile, they were asked to go out, to grow the food, to work on the electrical lines, to serve people in the ‘laptop class’ who could afford to stay at home, afford to not take the risk of being exposed to COVID. While the working class, the essential workers were asked to serve those others, to take those COVID risks.

And they did. And you could see in places that instituted lockdowns, in particular where I live in California, there was an enormous disparity in who suffered and died from COVID in the early days and actually even up to today. It was the “essential” workers, who were in reality, as far as society is concerned, not essential. Even if you were 65, you were asked to go deliver food to people who are in their 20s who had very low risk from COVID. You were asked to go do your job as a chef, as an electrical worker, as a line worker, as a member of the working class, regardless of the epidemiological risk you faced. The rate at which people living in poor neighbourhoods died from COVID in California was three times the rate at which people living in rich neighbourhoods died from COVID. That is in a developed country. Every developed country which has implemented sharp lockdowns has that same pattern of inequality.

It was even worse in the developing world. When the lockdowns in India were first instituted, 10 million migrant workers who work in big cities, live hand to mouth. They sell coconuts or something every day. Each day, after they sell their coconuts, with the money they made, they buy more coconuts they can sell the next day, and then they feed their family with the rest of the money. And that’s all they have. 10 million of them, overnight during the lockdown, were told to go home, to leave the cities.

The poorest in India died. While the Laptop Class stayed at home, migrant workers couldn’t sell their roadside vegetables. Forced to walk home penniless—up to 1000 miles–to their villages, they died en route. It was called The Trail of Tears.

What that meant is they had nothing. Whatever stock they had they couldn’t sell because no one was there to sell to because it was a lockdown, the laptop class stayed at home. The 10 million people were forced to go home either by bus or train, many of them by walking or cycling 1000 miles. One thousand people died en route in a very short period in that migration. People have called that the new Trail of Tears.

The effect on the developing world has been catastrophic. 100 million people have been thrown into poverty around the world as a consequence of these lockdowns, according to the World Bank. 80 million people have been thrown into dire food insecurity, meaning that they don’t know where their next meal is going to come from, and many of them go hungry. In March of 2021, the UN estimated that were 230,000 children that died of starvation in just South Asia alone. The people the hardest hit from lockdown are children and primarily poor children. Schools have been closed in places that have locked down–some places continuously, and they’re still closed. In Ghana, for two years, children have not had an education. Millions of children in Ghana will not go to school at all because of how long they’ve been out.

In the Philippines, there are kids who have not seen the light of day during the lockdown because they were born during the lockdown. In the United States, children who go to public schools (like me, who went to public school), like my kids who went to public school, for eighteen months were not allowed in classrooms. Richer parents can afford to support that. In fact, many of them did with hiring teachers who were not in school, who had time on their hands. Richer parents substituted for the harms of remote education: Poorer parents couldn’t.

Early in the lockdown in California, there was a story in San Jose Mercury News was about two Hispanic children, maybe six or seven years old. I’ll never forget the picture. Two children sitting outside of a fast-food restaurant, Taco Bell. Their parents had left them there. The story said that they were left there by their parents during the day with a Google Chromebook that their school had given them. They didn’t have internet at home. And so, their parents left them next to Taco Bell which had free internet. So they’re sitting on the curb going to school instead of actually being in a classroom.

Martin mentioned censorship. Not a liberal value, although weirdly it’s come to be seen as associated with the left. So, what you have here is a set of policies that should burn at the conscience of every single person who holds liberal values. So I’m pleased to be able to speak to this group which has throughout the pandemic understood this and has spoken out against it. The harms of the lockdown to the poor, the vulnerable, the working class are absolutely catastrophic. And it is going to take Right and Left together to turn on this.Actually, that is one thing I have been struck by is the set of alliances that have happened during this period that defy easy political characterization.

As Martin said, it was ‘left-wing’ governments in Scandinavia that avoided a lockdown, a right-wing government in the United States that implemented one, and the UK that implemented one. And yet, so much of the left has somehow failed to see this. So where do we go forward from this? I think the Great Barrington Declaration actually provides a path both for saving public health but also for the healing of society. The idea of focused protection is not just, an idea that works for a pandemic. It is the sane, humane idea to protect people most vulnerable and at risk from an infectious disease. But I think the idea of focused protection, is a more general idea, that the resources we have as society should be used to help the most vulnerable, the working class.

Thinking of creative ways to do that, political alliances which can do that, is something that I’m very passionate about. Thank you for your time.

Panel Discussion

Chair: Before we go to Q&A, would you like to interact amongst the three of you? Is there anything that has arisen from your speeches that you’d like to say to each other?

Dr Bhattacharya: Sunetra, I would love to hear how you think about what the scientific community is going to have to do and how it will heal. Because I believe that the rifts that we’ve seen among the scientific community will be difficult to come back from. What do you view as the path forward? And how do you see the role that scientists should be playing in the discussion as we move out of the pandemic?

Dr Gupta: It’s difficult to answer that question because, what this pandemic has done is highlighted how some of the scientific community operates. Which is through cartels and networks and kind of a particular form of tribalism has just been sharpened by this pandemic. Perhaps now, there’ll be a greater sense of accountability. And of course, I always look to the younger generation. It is the younger generation who have already been made uneasy by what they’ve observed in terms of people reviewing each other’s grants and papers and then the sort of timocracies that exist, will hopefully decide that’s not the way they want to do things. This is not how they want their lives to unfold within the profession. And so, I’m hoping that that change will come. Because they’ll be able to see, perceive that not only is this an unpleasant way to live, the consequences can be so damaging, and that’s what’s happened. That’s what we’ve just seen. We’ve just seen how these silly little cartels and timocracies have created the conditions that have led now to this devastating loss of life and unhappiness.

Dr Bhattacharya: I’ve been struck by how much the public at large has lost confidence in scientists, where once it was a pretty universal value that scientists were working for the good of the public. But now there’s scepticism about the products of science, about science itself, because the public sees scientists behaving so tribally–a tragic outcome of the pandemic because science depends on the public. If the public doesn’t support publicly funded science, it’s incredibly important that the public play a role in how science works so that it can be transparent because the discussions of scientists have such a tremendous impact on the impact of everyday people. So the collapse in faith in science by the people will have very poor negative repercussions in the future.

Dr Gupta: I think the people that need to pick this up and run with it. I am shocked that the institutions in this country, for example, the Royal Society, did not organize more debates. It’s one thing the Royal Society has always done very well. Whenever something controversial comes up, they organize a debate. And this time, they’ve just not done that. That’s the only way forward.

I mean, I’ve asked Neil Ferguson several times to have a public debate in which we air our views and then demonstrate to the public that, actually, we’re not there to insult each other, we just have different viewpoints. And he has never responded. But I think that’s what we need to do. We need to have debates which show that you can have different points of view and you can be respectful, and that perhaps that we are now prepared to abandon the old model of cartels and move forward in a different way; be accountable to the public.

Q & A

Chair: Thank you so much. We’ll open up to Q and A now. But I’ll say one thing. It’s interesting about the loss of faith in science because one thing that alerted me to the wrongness of this was the errant lack of science at the very beginning. Boris Johnson saying we’re on a war footing, ‘we’re going to fight the Germ, and we’re going to win’. But how does that work? We learnt in biology that coronaviruses are trillions of years old. It was this ‘production’ of science that turned many of us to lockdown scepticism from the beginning. OK, we have half an hour. Tara, we’ll start with you.

Audience Member One: Thank you so much all three for that talk, and for the Great Barrington Declaration. One of the things that worries me is not that we’ll come back from COVID with the lessons learned, but actually COVID is the model for public health (or anti public health) going forward. That we’ve just jettisoned basic public health principles, cost benefit analysis, straightforward stuff, screening work…what used to be how public health functioned.

My worry is that we’re not going to recover; this is the model for the future. Many European states are just doubling down, with vaccine passports; the same in some of the American states, you know, vaccine passports for five-year-olds in New York. I mean, it’s kind of lunacy. Britain has lifted restrictions at the moment but many places in the world are just sort of doubling down, you know, because states cannot admit this has been such a catastrophe, we just have to do more of it–the sunk cost fallacy.

That’s my fear. I want to hear the panel’s thoughts on that. And, quickly: Professor Gupta, I listened to your and Professor Heneghan’s discussion on the Popular Show. There was a very interesting point you made about what Dominic Cummings had done, the relationship of Dominic Cummings to some of the smears against you and your colleagues; Cummings contacting supposedly left-wing journalists to help attack the Great Barrington Declaration. You may not want to talk about that. But what do you think about that chance of COVID policies, unfortunately, being the model for public health going forward, rather than a more rational approach?

Audience Member Two: Thank you for everything that you have been doing. I want to get your insights about the nature of the scientific community. To expand on what Sunetra was saying. It’s very clear that as we move from Democratic contestation to technocracy as the basis of politics, the contestation that should be in the realm of democracy ends up in the sphere of science. Science itself becomes politicized.

Is it your impression that more scientists agree with you than are willing to say so in public? And if so, what does that tell us about the state of the scientific profession? Secondly, why have so many scientists been so pro lockdown to the extent that, as Sunetra said, they’re willing to make anti scientific, absurd statements in public? Is it because they have some taste of their own power, the revenge of the experts after years of populist insurrection against experts? Is it simple conformism? Again, what does this tell us about the nature of the scientific profession? And just to draw out what Jay was saying, finally, what does this mean for the status of science and scientists going forward? Because we cannot live without scientists or the scientific profession, especially on the left, we should be pro science, but it needs to return to its proper space in a democracy, which is informing–rather than substituting–public debate and democratic contestation. So how do we get science out of politics and the politics out of science?

Dr. Kulldorff: So, the pandemic is ending, and restrictions will end because of popular pressure on the governments. But the question about how public health will be in the future is a good, and important one. When writing the history of this pandemic, we have to make clear that lockdowns were a huge mistake, devastating for the poor and the working class and children as well as older people.

The history must be clear that this was a huge mistake, people must understand that, because that’s the only way we will make sure that this doesn’t happen again and that public health will get restored to its basic principles. That is a struggle and a fight that we have to continue with after the actual pandemic is over. That’s the first question. Sunetra or Jay can respond to the second one.

Dr. Bhattacharya: I’ll take a stab at the second question. So, the campaign to marginalize scientists who disagreed with the lockdowns is not probably as well known as it ought to be, but it should shock literally everyone. At the very highest levels of power within the scientific community, people like Francis Collins, head of the NIH, Jeremy Farrar, the head of the Wellcome Trust, that they specifically engaged the mechanisms of government of big tech and journalists to label any debate as illegitimate, that any scientists engaging in that debate or attempting to engage in that debate as fringe. Collins wrote an email to Tony Fauci four days after we wrote the Great Barrington Declaration calling the three of us fringe scientists. Now I’ll admit that you can call me fringe, I’m okay with that, but to call Sunetra Gupta and Martin Kulldorff fringe just does not make any sense. I’m sorry. I mean, they do teach at, you know, these minor institutions at Oxford and Harvard, but other than that, there’s nothing fringe about them. I’m kidding, obviously.

So, I think the very top scientists in the world who control the funding purse strings of so many other scientists who make and break the careers of other scientists, to engage in that kind of behaviour, it froze so many other scientists who saw the cost of speaking up, and even if they had reservations about lockdowns, which I believe many, many, many scientists did, they didn’t want to speak for fear of losing funding, for fear of social ostracization, for fear of losing their careers. And many people that signed the Great Barrington Declaration actually did lose their jobs, did lose grant opportunities, and did suffer from social ostracization, which is a very important part of science. Science is a social activity in the sense of you have to interact with other scientists in order to be productive and effective scientist. And it really depends on you got, you know, a successful scientist is a scientist who can convince fellow scientists that they’re right.

So, what you had is this kind of like absolutely extraordinary measures taken by the top scientists to essentially create an illusion of consensus that didn’t exist. That can’t go on. It’s not just simply- the cartel aspect of it is very important as Sunetra said, that, to me, that is even more basic. As the public, we expect the leaders of the scientific community who we entrust with tremendous value, in the United States, $40 billion that goes to the National Institutes of Health every year to fund scientific research, they need to act more responsibly.

And now the public needs to hold the leaders of [inaudible] so irresponsibly, freezing scientific debate and creating an illusion of consensus over lockdowns that didn’t exist and, as a result, the lockdowns being instituted. The public needs to hold those leaders accountable, and then [inaudible] in place so that science play a much smaller role in public health policy then because we now know that that’s a conflict of interest. If you control the purse strings of science, you can also end up with outsized influence on policy, whether or not you’re right. It happened during the pandemic.

Audience Member Three: I was reading about the Marek effect. Marek’s disease is a herpes virus in chickens. There’s a leaky vaccine which prevents death but not transmission. The Marek effect means that the disease became more serious and is now basically 100% fatal to the unvaccinated. So, given that the COVID vaccines are leaky in the sense that they (theoretically) prevent death and hospitalization but not transmission, are we risking something like Marek’s disease if we push them on people via vaccine passports?

Audience Member Four: It feels there is a lack of vocabulary with which to articulate competing values in the face of what amounts to an implicit ideology of COVID mitigation over everything else. Dr Gupta, you’ve mentioned, in a number of places, the idea of social contract for respiratory diseases. I wonder if you could elaborate on that idea?

Dr. Gupta: I can talk about Marek’s disease first. That’s a particular theory, proposed by Andrew Reed and colleagues, which rests on a set of assumptions concerning how virulence and transmissibility interact for a particular pathogen. Overall, I would say, no, I don’t think that more virulent strains of COVID—or SARS COV-2–are going to arise simply because they will do fine. The general idea there is that because a virulent strain is now no longer going to be killing as many people, it gains an advantage.

But that’s not going to be the case for coronavirus because, generally within an endemic state, coronavirus hardly kills anybody, itstransmission occurs in an arena where you don’t get much severe disease and death–it’s just when it filters into the vulnerable population, should they be immunologically largely naive or have progressed into immune senescence, that you get problem. But in an endemic state, that’s not going to be an issue.

Nonetheless, I don’t think there’s any logic to vaccinating anyone who’s not vulnerable, because this vaccine doesn’t stop transmission. So as such, I don’t think there’s a risk of Coronavirus becoming more virulent. I also don’t think that Omicron is significantly milder than the previous viruses.

All of this is down to the landscape of population immunity, herd immunity, that each strain lands in. So, the relationship between virulence and transmissibility is more complex than saying, oh, things normally become more transmissible and less virulent, or a leaky vaccine might make it more virulent. Actually there’s going to be very little variation in either transmissibility or virulence as the evolution of this pathogen population occurs.

With regard to the social contract, what I mean is that we live in a community, within which it’s very difficult to control a respiratory virus. Most kinds of infectious diseases are very difficult certainly to eradicate or even to suppress. However, what we do enjoy with most of them is the state of endemic equilibrium, where many of us are immune to further infection, which means that the risk of infection for the vulnerable is kept at its lowest possible level. This occurs at community and not an individual level: the whole process is a result of an interaction between those who are vulnerable and those who are not vulnerable, which is mediated by herd immunity.

Herd immunity in the general population keeps the risks low for the vulnerable population. What that means is that the end state we seek; the best possible solution is one that does involve people being naturally infected repeatedly. Now, so if that’s the situation, and that’s what we live with, with many of these viruses, knowing that that does mean that some vulnerable people will die, we accept that. We say this is the best we can do, because the alternative is locking everyone up which will cause more harm.

What that means is, that we are all participating collectively in this state of endemic equilibrium, which means that we are all going to have to take that risk of being naturally infected. Some of that infection is going to spread to some vulnerable people, and they’re going to die. Who takes the blame for that? The important social contract prospect is that we all take the blame for it. We disperse the blame. We do not locate it or condense it upon an individual. We don’t say ‘You killed granny’. We say ‘We live in a society where granny may get flu and die. Don’t visit granny if you’ve got a fulminant cold or whatever, don’t go give granny an infection when you know you’re infected. But overall, if she gets sick, don’t focus the guilt on yourself, even if you happen to visit a day before you knew you were ill and may possibly have given it to her’.

So, the dispersal of guilt is something that is inevitable, is I think a very big part of the social contract of infectious disease. We did the opposite of that during this pandemic. Rather than dispersing the guilt, we allowed those who are vulnerable to the psychological consequences of absorbing that guilt, we allowed them to pick that up.

Moderator: Thank you. We have 15 minutes more and can take 3 more questions.

Audience Member Five: Thank you. I wanted to ask about the significance of the severity of the virus. And also about people that you’ve met in positions of influence and power, in government or science, what do you think they actually believe? Do they believe in this virus? Because I was wondering if a very severe virus arose now, say 20% of the population was dying from it, do you think they would then turn to you and start taking you seriously? What do you think of the fact that a fairly unremarkable virus has allowed people to do quite extreme things that they actually wouldn’t have done, if it had been severe?

Audience Member Six: I also want to say thank you for bravery and courage and for inspiring so many people and also for being right. Around the question of individualism, I agree that virtue signalling is becoming an enormous problem but masquerading as communitarianism. In fact, it seems to me that the big problem surely is that individuals have been suffocated, and our whole autonomy and agency has been suppressed. And that’s a legacy of the idea of the public not being a political force or not being engaged. In terms of the question about the democratic discussion versus the scientific evaluation of things, it strikes me that what we need is a full reckoning now.

A proper full public inquiry that’s open not by a judge or civil servants but where the public demands to have a proper evaluation to avoid the very thing you’re concerned about: the lack of trust. Some people will say scientists are now seen as heroes. But there’s the lack of trust and a sense of retreat and scepticism, so I wonder if you think there needs to be a reckoning. Together want to have a full public inquiry where we demand and insist. Not done by the state but by the people.

Chair: So, we are being asked first about a sense of belief in the virus and how that’s affected policy and whether we should be having a public reckoning, as Alan says, to engage the relationship between democracy and science and engage the public more.

Dr. Bhattacharya: I apologize, could you repeat the first question please?

Audience Member Five: Whether people in influential positions believed in the severity of the virus, and whether if the virus had been more severe, would they have taken more notice of what you were saying and been less dismissive? Whether levels of severity of the virus was significant in the decisions that were made?

Dr. Bhattacharya: There was a dynamic throughout the pandemic that if you thought (even based on good solid scientific evidence), that the severity of the virus was less than the Black Plague, then you were being irresponsible. Perceived severity was used as a way to control human behaviour. I’ve seen this in argument after argument against the Great Barrington Declaration: the idea that if you propose something short of complete closure of society, you’re not taking the virus seriously. If you don’t reorganize your life, stay at home, don’t see friends, even if your loved ones die, don’t go to the funeral–if you’re not doing all of that, then you’re not taking the virus seriously or you’re letting it spread.

What Sunetra said about collective guilt is incredibly important. We don’t blame people for respiratory diseases because they spread so easily. It’s just part of being human in society. They spread, but instead we assign individual guilt. The key thing there is the fear around the virus. So, I did a study early on in the pandemic measuring the mortality rate, the IFR (infection fatality rate) from the virus. The World Health Organization early in the pandemic said 3-4% mortality from the virus, but turned out to be somewhere in the order of .2%. And for that, I faced absolutely enormous blowback: that I was minimizing the virus when, in fact, all I was doing was telling the results of a scientific study I’d done. There are now hundreds of studies that have verified it.

If the virus HAD been truly the black plague, would a lockdown have been have been the right thing to do? I still think the key thing, even with very severe disease like this, is focused protection. You have to figure out who’s most vulnerable, because in order to have the best care for the vulnerable, society needs to keep going. And the set of people who are least at risk, if you are working at it from an ethical perspective, are the ones who bear the responsibility of that, whereas the ones that are most at risk are the ones who should be protected. So, I think that it’s not so much the severity per se but rather the characteristics of the virus such that you understand who’s vulnerable and who’s not so that you can organize a response that protects those who are most vulnerable, while the ones who are least vulnerable continue with the business of keeping society afloat so the vulnerable can live.

Dr. Gupta: Shall I take the question? Because I’ve thought quite a lot about the second question about what is individualism and what is liberty, and I think they actually operate on different axes. So this is something loosely adapted from Mary Douglas’s typology of different axes on which people’s opinions lay, and her original typology has it divided into quadrants. One axis goes from hierarchical to egalitarian and another which goes from individual to communitarian. You can think about where people’s opinions lie within that. So largely academia used to be kind of communitarian but quite hierarchical, but now it’s moved, to being individualistic and has remained hierarchical, which is very unfortunate. But there is a third axis which actually then maps more to the liberty, equality and fraternity ideas.

The third axis is the liberty axis; from libertarian to authoritarian. So, I think that a lot of the problems that arise are in not distinguishing between these different poles. So you can be communitarian but want liberty. And that is not individualism. Individualism is different from wanting liberty. So, I think that it’s very important to settle those axes in our heads and say what we don’t want is authoritarianism. So, it’s not okay to be authoritarian. We don’t even want communitarian authoritarianism. And we also don’t want individualistic libertarianism. So, I think the landscape is a lot more complex. We need to disentangle the idea of individualism from freedom. So sometimes, I think am I interested in freedom?

I’m interested in human dignity and the extent to which freedom enables that.

Freedom in itself I don’t think is such a useful goal.

Chair: And this really fits in with discussions that LLS has had. We are a very loose network, but we have discussed what the role of maybe a more libertarian left might be, which incorporates individual liberty and a responsible communitarianism that doesn’t involve state overreach. It’s finding the balance which we have lost. It’s an interesting, necessary discussion. Thank you for the question. We have time for two more questions which I’ll ask the panel to answer briefly.

Audience Member Seven: I can’t imagine what things would have been like without the Great Barrington Declaration. I was wondering, in relation to the slurs and the slander that you’ve had to deal with, what regrets you have, what would you do differently in terms of the presentation? Is there anything that you would do differently?

Audience Member Eight: Hi. I’m very glad I’ve got a chance to ask this question because it’s specific for you three and the medical and scientific community in particular, and it could offer a way forward to unite people on different sides to argue for a more productive future. My question relates to NICE (National Institute for Clinical Excellence) which approves UK treatments, pharmaceutical interventions, cancer drugs–famously, when people argue about which drugs are worth prescribing or not. And then also NPIs. Non-pharmaceutical intervention. An article in Daily Sceptic by a London based doctor (well over a year ago) pointed out that if lockdowns were a medicine, they would be analysed in such a way. You’d look at the pros and cons. And if it was found that such and such a medicine, might be good at reducing effects of coronavirus, but at the same time, it would stop children going to school, stop cancer diagnoses being made, cause domestic violence, etc., etc., it would never be passed.

So, my question is could there be a way forward? Is there already a movement in the medical and scientific body to argue that NPIs should be subject to the same criteria as pharmaceutical ones? If there isn’t, could there be?

Dr. Gupta: Martin, I think you should come in.

Dr. Kulldorff: On the second question, I think that any public health intervention should be based on solid evidence. And it can’t be exactly the same as a pharmaceutical drug because a pharmaceutical drug would need randomized, placebo controlled, blinded trials, which you cannot necessarily do for all interventions. But all interventions should be based on solid evidence. Also, I think that when it comes to public health, we have thrown out the principles, but there are three really big important ones that we always have to consider and which are the main culprits in pandemic policy.

One is you can never focus on only one disease like COVID. You have to look at public health as a whole, including the collateral public health damage that Sunetra talks about and that organization Collateral Global is studying. The second one is you can’t be short term. You have to look at the long term. So, you can’t only think about what’s going on now. So infectious diseases or {inaudible} conditions like cancer, where lockdowns won’t influence short term prognoses but more cause those who would have lived 15 to 20 years to die from cervical cancer three or four years from now. And the third one is that public health is about anybody, not just the laptop class of scientists, journalists, bureaucrats and so on, but everybody. Working class, the poor in the third world. So public health always has to consider the whole population. And those are three fundamental principles of public health that were thrown out the window during this pandemic. And because of that, the working class was thrown under the bus.

Dr. Bhattacharya: Why don’t you take that one?

Dr. Gupta: I think there was never any question in any of our heads, those of us who engaged in this knowing full well what the professional costs would be for us that, this was the only option. There was no other alternative. So, I certainly don’t regret any position that I’ve taken. I’m not saying I wasn’t wrong on certain counts. I’m sure we all were. I’m sure I could have articulated things better; anything I’ve said in the last hour or so I could have said better. You can always plan something better. In some ways, I’m glad that we didn’t have some sort sophisticated PR machinery behind us to make sure that the message landed in the right quarters in a way that we couldn’t be smeared, and maybe in some ways that was inevitable and a demonstration of where we’re coming from.

We were not an organized campaign or a cartel. Martin and Jay and I had never met until in October of 2020. We weren’t aware of each other. We had nothing to gain from collaborating or endorsing each other. We acted out of our principles, and I think we abide by them.

Chair: Just to finish, I want to say it must be incredibly frustrating to see the laptop class gradually come around to your principles and the Guardian say say, oh, the Great Barrington declaration, they don’t really exist, but to repeat exactly word for word what you said a year and a half ago. I think in terms of the Lockdown Sceptic movement, I think we need to think about the psychology of people never admitting they’re wrong. It’s just such a thing. It’s just a thing whatever side of the divide you’re on. And if people could occasionally admit they’re wrong, I’m not talking to you, Guardian or BBC, if people in the media could admit they were wrong and look to visionaries and look to early adopters of correct paradigms, we would be much further ahead.

I have a couple of announcements. But first, I just want to thank, from the bottom of my heart and from bottom of all our hearts, Sunetra, Martin, and Jay, for joining us today.

Dr. Kulldorff: Thank you, everybody. And thank you for all the things you’re doing. And keep up the good work.

Chair: Thank you, and get back to sleep! Thank you so much, Martin, and hopefully we’ll see you at other meetings in the future. A few announcements: Sunetra, Jay and Martin’s Collateral Global charity is an excellent choice of charities to donate to and support. Sunetra can be here to chat for another five minutes.

We’ll resume at 2.20 after lunch for the Effective Campaigning panel with Big Brother Watch, Together Campaign, a clip of NHS 100k campaigners, for an exciting discussion on effective campaigning in the months ahead. We’ve had some pushback, and we need to keep up the pressure.